What passes for eroticism these days? In an online world swamped with A.I. porn and social media influencers tripping over their ringlights to dole out intimacy tips, the definition of what is—and what is not—erotic in the twenty-first century is increasingly difficult to define. Leave it to London’s Courtauld Gallery, then, to take us back to simpler times. “Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams” brings together artwork originally chosen for the “Eccentric Abstraction” exhibition at New York’s Fischbach Gallery in 1966. Curated by art critic Lucy Lippard, Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse and Alice Adams were the only women included in the New York show, and this retrospective strips out their male counterparts to let the three artists’ work shine. The title, incidentally, comes from the phrase Lippard used at the time to qualify and explain the artworks included.

Given the period the exhibition represents, the eroticism here is of the “oh my” variety—the kind of coy erotic experience that is gently hinted at rather than waved in viewers’ faces. At times, the coyness is so dialed up that it’s difficult to locate the artworks’ erotic heart. Displayed in a room of their own, the succession of untitled drawings Bourgeois made between 1968 and 1971 involves squiggly loops and jagged lines that could be anything from rocky landscapes to layers of flower petals. Is this Bourgeois finding eroticism in nature’s construct? Also, Alice Adams’ Resin Corner Pieces—a collection of seven sticks leaning against the wall—look more like the beginnings of a fence-building project than a treatise on erotica. The sticks are prophylactically covered in a thin layer of latex, though.

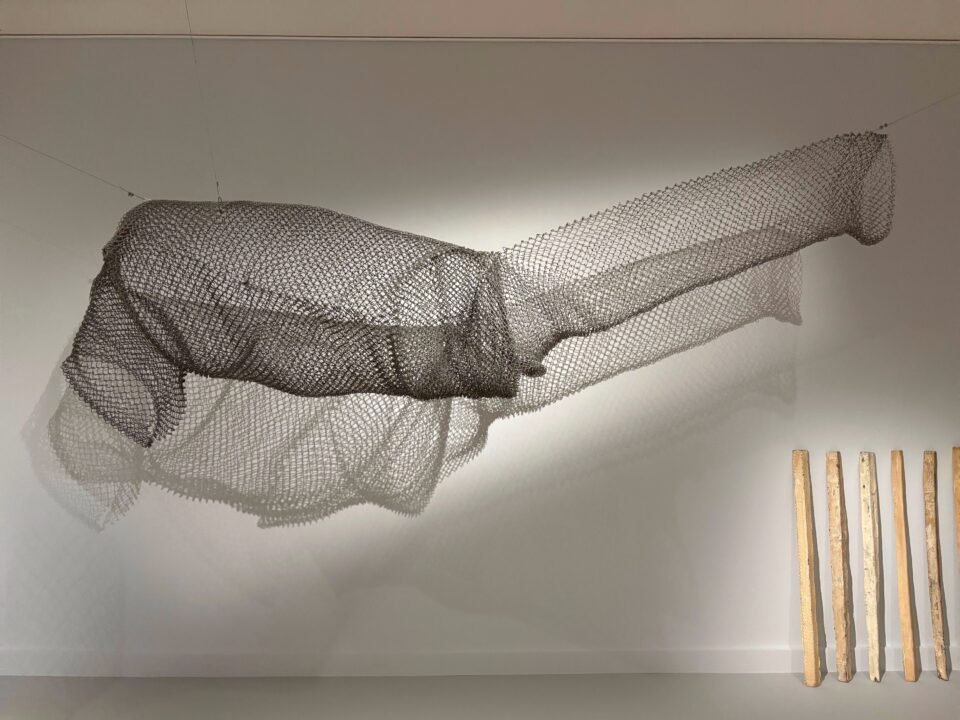

Thankfully, most of the artworks fulfil the brief completely. Big Aluminium I, Alice Adams’ twisty mesh tube from 1965, is a thing of great wonder. Dangling from the ceiling, it could be two fishnet stockings intersecting and has an alluringly sanguine feel, perfectly encapsulating how eroticism can be implied in abstract art. Also, there is something equally as alluring about her Threaded Drain Plate, created in 1964. After all, this is just a bunch of metal cord pushed through the holes of a metal plate. But somehow, it has a certain come-hither swagger about it. It’s easy to imagine the thing waggling an eyebrow suggestively while offering you a cigarette.

Created throughout the 1960s, Louise Bourgeois’ series of Hanging Janus sculptures mashed together male and female genitalia. The Hanging Janus here is firmly of the male variety. Fillette (Sweeter Version), made towards the end of the decade, continued her interest in this conflation. Most obviously phallic, the artwork’s name (fillette can be used to describe a young girl) and the thought that the pair of spheres at its base might represent female hips (as well as the obvious) introduces a seductive ambiguity. There are more implications and suggestions in Adams’ 22 Tangle, as a red woven wire circle slides up a mesh tube. Two Eva Hesse artworks from 1966, both untitled, raise the erotic game. For one, objects resembling a languid vanilla pod and a comely pear are just about touching, the pod slightly—deliciously—curling around the pear. Fruit and fauna have been used as erotic metaphors in art since the Renaissance, and Hesse’s second 1966 piece adds to the timeline, as three plum-shaped spheres hang in a webbing sack. Elsewhere, Adams’ Sheath from 1964 is reminiscent of a knotted, knitted primitive condom. Louise Bourgeois’ Tits from 1967 speak for themselves.

As this coyness feels rather dated, historical context is vital. Alice Adams was New York City born and bred, and Bourgeois and Hesse had become American citizens after relocating from France and Germany, respectively. Second-wave feminism was slowly gaining traction in America as advocates fought for substantive gender equality, but the three artists still had to spend their early careers proving women artists had just as much right as men to investigate themes of sexuality in their work. By the mid-1960s, Bourgeois had achieved a prominent position as an artist of renown, despite the male-dominated art world and social mores that expected her to stay barefoot and in the kitchen. Eva Hesse’s short career (she died of a brain tumor in 1970, aged thirty-four) was blighted by mental health problems as well as gender prejudice, yet her use of unconventional materials added new meanings to three-dimensional artwork. Alice Adams’ artwork shown in the “Eccentric Abstraction” exhibition introduced a seismic change of direction. Here was an artist who brought a human warmth to the prevailing interest in architecturally influenced minimalist sculpture—and Alice is still making art in her early nineties. Asked later about the Bourgeois, Hesse and Adams artwork she picked for the original Fischbach Gallery show, Lucy Lippard said, “I can see now I was looking for feminist art.”

This is, admittedly, a pretty small exhibition at just two rooms; three if you include the space with the Bourgeois drawings. That said, the admission fee includes entry to the rest of the Courtauld’s galleries, where you can view Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, two of Gauguin’s Tahiti paintings, several Degas canvases, some Cézannes, a Van Gogh self-portrait and many other works of note.

“Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams” is on view through September 14, 2025, at the Courtauld Gallery in London. Advanced booking is advised.

More exhibition reviews