Michael Segura, executive director of the Garcia Center for the Arts, didn’t mince words when IECN pointed out the chorus of social-media comments claiming arts investment here is a waste of money. “Are the people saying this the police?” Segura quipped on IECN’s Inland Insight podcast on July 18th. “Our police take so much of our budget in a lot of communities. If you want to make communities safer, invest in social programs — arts and culture included — that give people alternatives to being on the streets.”

Segura joined the podcast to discuss the center’s operations, the challenges of funding, and controversies ranging from gentrification fears to public safety concerns. Hired in January 2025, he has spent the past six months restructuring programs and building systems for sustainability, data collection and community impact.

Founded nearly a decade ago by Ernie Garcia, the nonprofit center leases its main building from the San Bernardino Valley Municipal Water District for $1 per year and owns the adjacent lot that houses its community garden. The garden offers seasonal produce, a seed library and, eventually, culinary workshops aimed at teaching residents how to prepare fresh food — a component Segura says can help address food‐desert issues in the city.

“We grow together,” Segura explained. “We’ve had peaches, nectarines, grapes, lettuce and strawberries. Soon we’ll be teaching cooking classes so people know what to do with the fruits and vegetables they pick.” He added that the garden program is funded in part by a stipend from the IECF’s CIELO Fund, but is seeking broader health and nutrition grants.

Building Sustainable Programming

Upon arriving at the center this year, Segura said his first priority was “listening” — holding listening sessions with instructors, artists and community partners to understand needs and gaps. That led to the creation of an educational council, designed to provide local teaching opportunities at the center, known as the Creative Instructor Program. This program is said to give locals an opportunity to teach arts to the community, while receiving a stipend, and gaining classroom experience. “Some creative instructors will use this as a leap pad into primary school teaching or university positions,” Segura noted.

He also helped launch the “Mercado 536,” a permanent artists’ cooperative retail space where makers can sell jewelry, pottery, photography, leather goods and beauty products. Under a new co‐op model, artists keep 100 percent of sales revenue in exchange for a modest $40 annual membership fee and periodic volunteer commitments to staffing the store. “We want to help build the local economy,” Segura said. “When you buy local, you support your neighbors — that’s the mission of Mercado 536.”

Ticketed workshops remain as a revenue source to pay instructors and cover utilities, but Segura plans to shift toward stipends and free community events as the center diversifies funding through private foundations and local partnerships. Discussions are underway with Cal State San Bernardino, University of Redlands and the Inland Empire Small Business Development Center to offer entrepreneurship courses tailored to artists and makers.

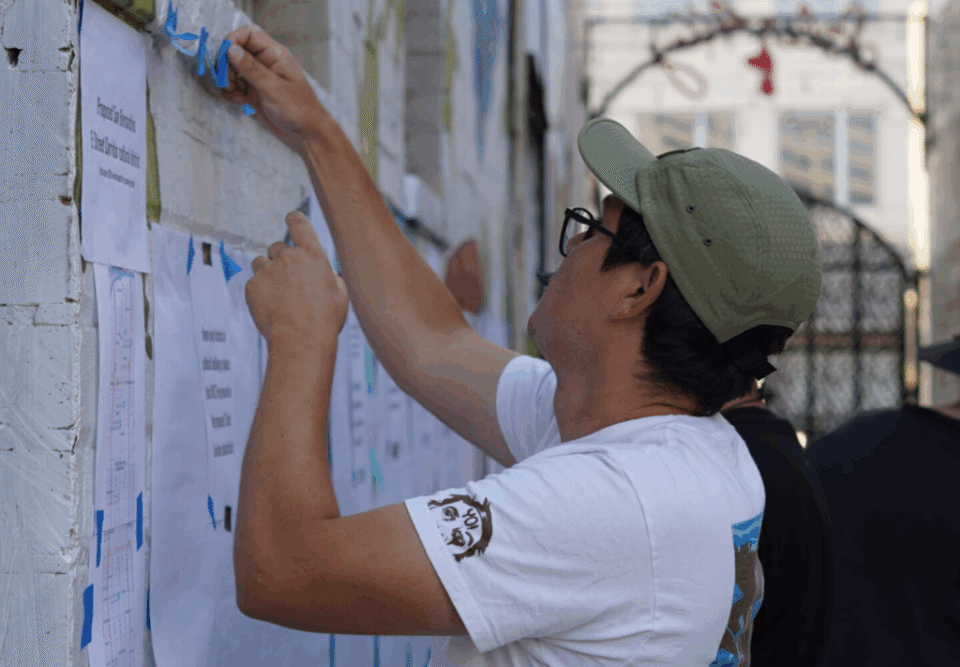

Controversy Around Gentrification

Questions about gentrification emerged when podcast hosts asked why artists often become early indicators of neighborhood change. Segura acknowledged the dilemma: “When you bring crowds — people coming for shows, selfies in front of murals — it becomes ‘trendy’ and then coffee shops and vendors follow.” He pointed to recent debates over “selfie murals” that attract outside visitors without reflecting local culture.

To counteract displacement, Segura advocates for artist‐specific affordable housing. “Cities like Pomona and Pasadena have crafted affordable live‐work spaces for artists,” he said. “If you provide housing and studio space before that wave of gentrification hits, you protect the very creatives who shape community identity.”

He also stressed the importance of local arts policy. “We need impact fees tied to hotel taxes or new construction projects — dedicated arts funding that can’t be diverted to the general fund,” Segura said, referencing past city decisions that funneled arts impact fees into unrelated budgets.

Ensuring Safety and Accessibility

The Garcia Center’s 1920s-era building, surrounded by a 5-foot-tall iron fence, has not been immune to safety concerns. Segura disclosed plans for a comprehensive security upgrade, including electronic door locks and surveillance controls that track who opens each door — at an estimated cost of $82,000. “It’s pricey, but necessary,” he said.

He even stated that the center has a safety plan in case ICE shows up, noting federal intervention feels like a bigger threat than local vandalism when he was asked about general security. Segura also described a designated “safe area” within the center and said the organization would hire security for events expecting more than 100 attendees.

To improve access, the center is in talks with local developer David Freeman of Realicore Real Estate to lease the empty lot behind the building for up to 60 parking spaces — a critical need for evening performances and weekend workshops. Initial permitting and paving estimates run around $30,000, and Segura and city officials are exploring less costly surfacing alternatives.

Funding Pressures and Future Plans

With state and federal grant programs tightening under the Trump Administration, Segura is pivoting toward private philanthropy. “Grants are great, but they come and go,” he said. “We need a diversified portfolio: tickets, memberships, private foundations, corporate sponsorships and event revenue.”

He also plans to introduce a coffee shop in the garden space, partner with local brewing collectives, and expand studio rentals with a membership model.

Arts Advocacy and Community Engagement

Segura wrapped up the podcast by encouraging arts supporters to apply for seats on the city’s Arts and Historical Preservation Commission.

As the Garcia Center approaches its 10th anniversary in November 2025, Segura envisions a multigenerational, equitable arts campus that nurtures local talent, fights displacement and fosters creative entrepreneurship. “Creativity isn’t just for ‘artists,’” he said. “It’s essential for innovation in every industry. Investing in art is investing in our future.”

The center currently features an auditorium; a gallery space; a public art library; ceramics and glass-blowing studios; and two vacant workspaces.

The Garcia Center for the Arts is located at 536 W. 11th Street, Suite 1, San Bernardino.

Listen to the full podcast here.